|

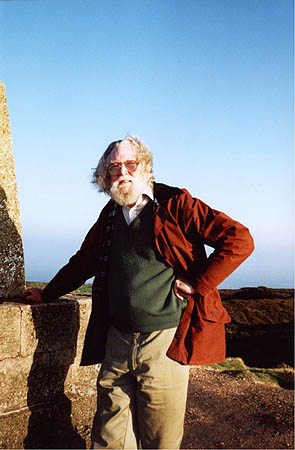

picture from Anne Hone |

Anonymous |

|

David C.B. Mills page 6 |

Page 1/Page 2/Page 3/Page4/Page5/Page6/Page7

|

picture from Anne Hone |

Anonymous |

|

picture from Anne Hone |

A note from Elizabeth Gatland (a.k.a. E. Wein) 5/20/04

David Mills: A Tribute to a Friend

The generosity of you

went unacknowledged as I took

with the blithe gratitude of youth,

assuming it my due.

Your gifts were immaterial.

You went unshod and scorned possessions.

Yet everything you gave was precious

beyond parallel:

Fireworks and whiskey, breakfasts, Brel

-I warehouse now the images-

Our long, diverted voyages,

and daffodils, and bells.

These, with your giverís heart, are gone,

consumed or withered, silenced, black.

I cannot give such kindness back.

I must pass it on.

(For DSM, with love from EWE)

|

*****

In the minutes after I heard the news that David Mills had died, I was overwhelmed by memories of the two aspects of his personality that had characterized our friendship: his exhuberant, youthful taste for laughter and adventure; and his enormous generosity. I became friends with David not quite fifteen years ago, when we were both ringers at St. Martin-in-the-Fields in Philadelphia. I was a young graduate student, and he had grown-up children, but the St. Martin's ringers were a mixed bag, and age gaps didn't seem to bother any of us. David was living on his own, though still very involved with his young family not far away. In all the time I knew him his personal living space was spartanly furnished, as though he utterly scorned possessions. His walls were at first decorated with jigsaw puzzles (one piece assiduously missing from each), and later with his ridiculous and expansive collection of stolen home security system alarm signs. Yet he loved beauty, and beautiful things, and creativity; he acquired sculptures and paintings by friends and admirers, and eagerly displayed them to visitors; with his sons Gerald and Alexander he built an exquisite water garden in memory of his second wife; one of his prize possessions, I am sure, was the set of handbells he acquired in recent years. These are all things that can, indeed must, be shared, and I think that is why he loved them (he rang those handbells at my wedding). David loved sharing. He paid for about three-quarters of the alcohol I consumed during my years as a graduate student, he took me to the opera on numerous occasions, he sublet my apartment from me when I went to England to do research for my doctoral thesis, he took care of my cats for five years when I moved to England permanently, he made tapes for me, he gave me flowers, he wrote rare and wonderful and screamingly funny poems. He did me little, quirky kindnesses. He once surprised me with a pretty notebook I had admired and been too stingy to buy for myself. When Sara, my one-year-old daughter, began to weep in a tea garden on the Thames because they wouldn't sell us milk for her to drink, David poured the contents of his own pitcher into Sara's cup instead of into his tea. Once, in a fancy cheese shop in Philadelphia where they were advertising caviar on sale at $250 a pound, I said, as a joke, "David, buy me a pound of caviar." He asked in alarm, "Do you really want it?" "Of course not, you idiot," I laughed, and later that day in front of a flower shop demanded, "David, buy me a cabbage!" Now he was on to me, and laughed it off. He got his own back, though, two days later; he turned up on my doorstep offering me an ornamental cabbage as a gift. That was a long time ago, and it was all in play. But I believe, to this day, that if I had really wanted that pound of caviar, David would have given it ungrudgingly. I feel as though my friendship and company cannot possibly have been adequate payment for his generosity. And yet, thinking over the things we have done together, I know that he treasured my company. I took him punting on the Cherwell in Oxford, and he took me punting on the Cam in Cambridge in fair exchange; David came along with my husband and I when we flew from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Kalamazoo, Michigan, in a small plane; David and I went on numerous long-distance ringing outings together, alone and with other traveling companions, and we detoured all over the place to picnic and sight-see and find pubs and seafood restaurants. He splashed about with my toddling daughter in a wading pool in a Cambridge park. He sat on my grandmother's porch in Pennsylvania drinking bourbon with her. I hope, and must believe, that he enjoyed these spontaneous moments as unstintingly as I did. I will leave it to others to detail his life, his work (in which he was deeply absorbed, and at the end deeply frustrated), his dedicated contributions to the North American Guild of Change Ringers as ringer and steeple keeper and Peal Secretary, his families in Britain and North America. I feel that I have only ever been on the periphery of these things, which constituted the major part of his life. My friendship with David is all I really know of him. But it affected me deeply, and it breaks my heart to have lost him. In this, I know, I am not alone.

E. Wein

|